In the 2023 song “God must hate me,” Catie Turner writes:

“Do you ever see someone and think ‘Wow, God must hate me’

‘Cause He spent so much time on them and for me, He got lazy

Got ample mental illness personality flaws

While their only flaw seems to be is that they have none at all…

I don’t know what I believe

But it’s easier to think

He made a mistake with me.”

Have you ever felt anything like this? Although religion and spirituality can be helpful to people, they also can be sources of stress or even trauma. These lyrics demonstrate the emotional power of what psychologists often term “religious and spiritual struggles.”

What is a Religious or Spiritual Struggle?

A religious or spiritual struggle involves a tension or conflict an individual may experience in relation to what they consider sacred. For instance, like in the song lyrics above, a person may feel angry, disappointed, abandoned, or rejected by God. Someone may wrestle with their beliefs or the ultimate meaning of their lives. An individual also may be upset by interactions they’ve had with others within religious or spiritual communities or feel hurt or offended by the teachings of a faith.

The Effects of Struggling with Religion and Spirituality

Research conducted across a variety of contexts and groups consistently reveals how religious and spiritual struggles predict poorer mental and physical health. For instance, individuals who report more religious and spiritual struggles also tend to report more anxiety, depression, and suicidality as well as lower satisfaction with life and overall happiness.

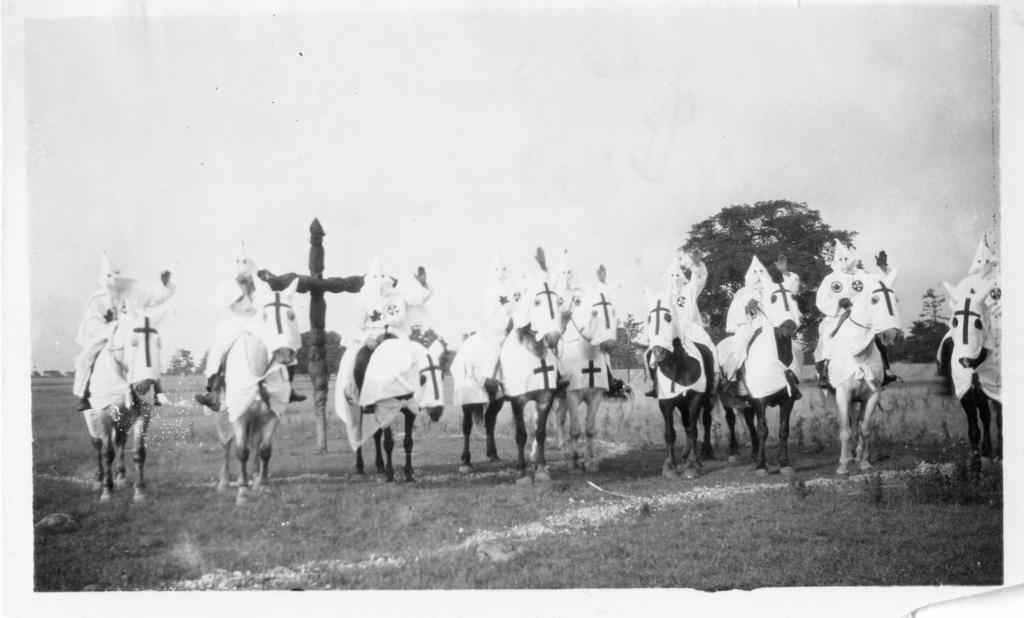

Experiencing religious and spiritual struggles may also underlie why many people disengage from a religion, an increasingly common occurrence. For example, people may withdraw from a religion when they feel negative emotions toward God, such as in the lyrics that opened this article. As another example, individuals may pull back from religion if they experience judgment from others or disagreement about political issues in their religious community as well as when they feel dissonance about belonging to a group they feel has perpetrated prejudice or violence.

Given all this, what could help people wrestling with stress and trauma associated with religion and spirituality? Below are six suggestions informed by the research on this topic.

6 Ways of Coping with Religious and Spiritual Struggles

1. Realize you’re not alone. Experiencing religious and spiritual struggles appears fairly common. In one study, for example, when a national sample of adults were asked to name a specific religious or spiritual struggle they experienced in the past few months, about 40% could do so. Furthermore, many of the heroes of religious faith – from Job to Jesus to Mother Teresa, in the Judeo-Christian faith, for instance – also struggled with matters of the sacred. Realizing this may help decrease the sense of guilt, shame, or moral unacceptability you may feel.

Continue reading